Who are we setting out to be online? By whose power are we gaining followers? How are we influencing others to spend their time?

These questions have been assailing me since I started sharing my writing on

.Also, in case you haven’t noticed, ever since the Internet has started expanding, so has the potential to turn a profit with online content.

So what happens when the people of God start making their living on clicks and when their success is measured in follower counts and views?

When the cards fall and the chips are down, who are we writing for?

The McDonald's Video Game

As a kid, I passed countless hours on AddictingGames.com (I wonder why), and had a strange affinity for games of tactical domination. (This started as a fascination with Roller Coaster Tycoon, then Tower Defense, then Farmville when Facebook became popular, and later games like Pandemic 2).

I went through a season where I couldn’t get enough of the McDonald’s Video Game. The non-licensed marketing and management simulator was later renamed Burger Tycoon (probably due to copyright issues) and boasted a whimsical, irreverent veneer of subtly anti-capitalist provocation.

I liked it because it was funny, required strategy, and made me think about the implications of running a world-wide fast food empire.

According to Wikipedia,

The game presents the player with four views: the farmland, the slaughterhouse, the restaurant and the corporate HQ. Through each of these views, decisions can be made which will affect the fate of the player’s company. In the game, the player takes on the role of a McDonald’s CEO by choosing whether or not to feed the player’s cows genetically altered grain, plow over rainforests or feed the player’s cattle to other cattle (a practice known to spread mad cow disease). The player can also choose advertising strategies and public official corruption to counteract opponents of the player’s actions.

It was a game of risk analysis. That was compelling enough, but the moral implications made it even tastier (no pun intended). After many long hours of study, I finally developed a succesful model of gameplay. I had maxed out the corporate profits, and a smiling Ronald McDonald met me with a message saying that I had beaten the game.

I had been in charge of McDonald’s. And I had beaten the game. I had conquered the world of fast food.

What was this exposure to dubious corporate decision doing to my young, impressionable brain?

A Tower to Escape the Flood

We are building a religion

We are building it bigger

We are widening the corridor

And adding more lanes

— Cake, Comfort Eagle

Man has always sought his own way.

The Revelation of John names the unseemly auspices of man’s delusions of grandeur in chapter 17. There, the Lord explicitly condemns MYSTERY, BABYLON THE GREAT.

Almost 2,000 years later, we are still left with the same question.

What the heck did He mean by that?

To understand, let’s go back, all the way back, to the namesake of Babylon:

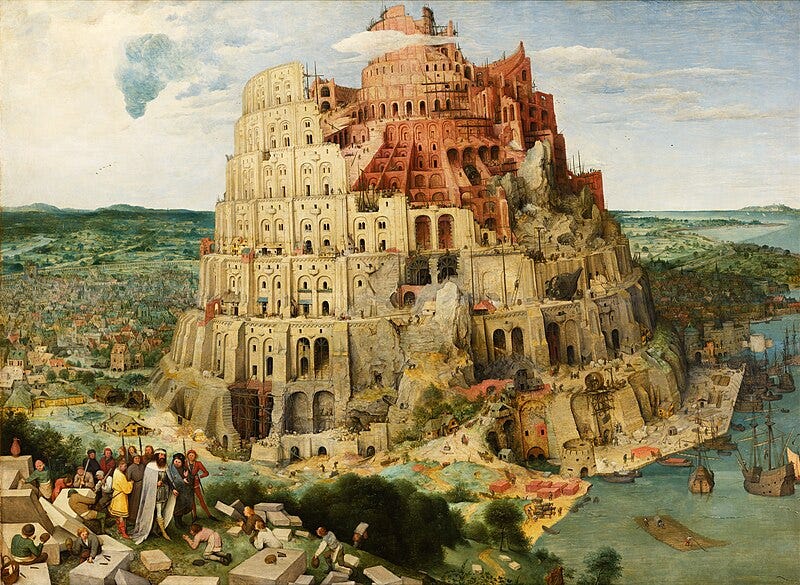

I’m talking about Babel. On the Plains of Shinar, man baked bricks and tried to build a tower to Heaven. But God crushed his plan and confused his languages1.

The story of Babel alludes to the folly of usurping rather than obeying the call of God.

But the historian Josephus adds an interesting layer of detail to the Babel dilemma.

He speaks of the inhabitants of the world ignoring the rainbow, a promise of God’s peacefulness towards man, in favor of a bigger, better security: a man-made structure that would underwrite their future safety and sovereignty:

They settled on the Plain of Shinar, and grew so numerous that God counseled them to send out colonies. In their disobedience, they imagined that God was trying to divide them and make them vulnerable to attack! So they followed Nimrod, the grandson of Ham, who set up a tyranny and began building a tower higher than any water could reach in case God ever wanted to flood the earth again.2

This is hard to believe! These people knew the will of God and expressly rejected it!

How could they be so naïve? We would never fall for this today.

Or are we partakers of the same faulty reasoning, stacking our posts higher than Heaven in hopes of averting the crisis of the judgment on our futile approach to the Gospel?

If so, we’re guilty of a Babylonian works-based salvation.

Here’s what we often miss, and what Josephus tactfully brings out: there was fear of God in Babel, but it was not a healthy fear. It was a fear like that of rebellious children about to get caught stealing cookies from the cookie jar.

Are we stealing the Lord’s glory by ignoring His promises of judgment?

Are we hardening our hearts like clay bricks and bitumen?

Have we forgotten the lessons of Job?3

A Tower to Heaven

Another key piece in the Babel story is the understanding of the power of our words.

In verse 6, we see the Lord’s reaction to the building project of the men of Babel:

And the Lord said, “Indeed the people are one and they all have one language, and this is what they begin to do; now nothing that they propose to do will be withheld from them.

Was the Lord worried that people would dethrone Him and rule Heaven and Earth in His stead? Of course not — how could they?

But what they were capable of doing was controlling and subduing one another for the purposes of sin, purposes that had come to bear only three generations earlier, during the days of Noah.

Do we see the same pride as we did on the Plains of Shinar at work in the hearts of the sons of men today?

Recently asked by George Janko why he wouldn’t explicitly claim the title of Christian, Jordan Peterson asked what it meant to be Christian.

In an AMA he did on Reddit seven years ago, Dr. Peterson said something similar, that he would rather live Christianity out than claim it with words.

I get it. It’s tricky to identify with a movement if you don’t adhere to its core teachings to the best of your ability. Or even if you do, really. Especially one as intellectually reviled as Christianity.

But at what point do we allow ourselves that leeway? When do we drop the façade and simply name it, claim it?

We call ourselves Christians when we give up our name for Someone else’s.

The Babylonians knew the power of a name (v4):

Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower whose top is in the heavens; let us make a name for ourselves, lest we be scattered abroad over the face of the whole earth.

In part, I agree with Jordan Peterson — we must count the cost. We must know what we are signing up for. In that interview, JP asks a great question: are Christians those who would willingly go to the Cross?

Well, are we?

But the problem with his answer is twofold:

One is that we don’t get washed clean before getting into the shower. In other words, to experience the cleansing power of Christ, we have to be in Christ.

Two is that there is power in our words.

Words are action. Words create. It is by the Blood of the Lamb and the word of our testimony that we are saved4. But in a naturalistic worldview, words are just inconsequential soundwaves. And to a naturalist, they cannot change anything.

But words are the guarantee of our living testimony. The power of life and death is in the tongue.

Let’s write as if our life depended on it.

Writing for Babylon

This is what we’re up against.

Young people are being exposed, just as I was in the days of my fast food world domination, to the economy of Babylon.

Only now, they are being taught to buy and sell influence, likes, and subscribers.

Kids younger and younger are focusing on their online personae more and more5.

As writers, what are we doing to expose this?

What is our writing setting out to do?

Do our posts read like click bait, or do they make chains break?

Are we the fly paper in the algorithm? Or have we come to set the captives free?

Are we writing for Mystery Babylon, or for the New Jerusalem?

As Christians, we’re called to choose in this life, and be spared God’s justice in the life to come. That choice is painful because requiring trust, or faith, in the things we can’t see.

The paradigm shift starts within ourselves. And it starts by recognizing that God calls us to be a holy people.

And the merchants of the earth will weep and mourn over her, for no one buys their merchandise anymore: merchandise of gold and silver, precious stones and pearls, fine linen and purple, silk and scarlet, every kind of citron wood, every kind of object of ivory, every kind of object of most precious wood, bronze, iron, and marble; and cinnamon and incense, fragrant oil and frankincense, wine and oil, fine flour and wheat, cattle and sheep, horses and chariots, and bodies and souls of men. (Revelation 18:11-13 NKJV)

The adage of the digital age says that if you don’t know what you’re buying, you’re the product being sold.

With this in mind, we Christian writers who care enough to do so ought to continue to write, not fast food for the eyes, but chicken soup, so to speak, for the soul that is longing for nourishment.

Not out of a sense of superiority or false righteousness, but because Someone gave it to us first.

Prayer

Father, we thank you that we are saved by grace through faith and not by works, lest any man should boast. We know that You credited faith as righteousness to Abraham, our father. Gather us now into the family of believers worldwide, Lord God. Rule over us by giving us Your name to reign in our hearts. We pray this in Jesus’ holy name. Amen.

Genesis 11:1-9

Josephus, Flavius, ed. Paul L. Maier. Josephus: The Essential Writings. Kregel Academic & Professional, 1990.

Would you indeed annul My judgment? Would you condemn Me that you may be justified? Job 40:8

Revelation 12:11

For a thoroughly shocking and scrupulous account of the changes going on in our children, I would recommend reading Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation.